Although it’s been less than a week since the global outbreak of monkeypox (MPX) gained traction, we’re already gathering important clues thanks to timely and incredible collaboration around the globe. Here is the latest state of affairs.

Case Surveillance

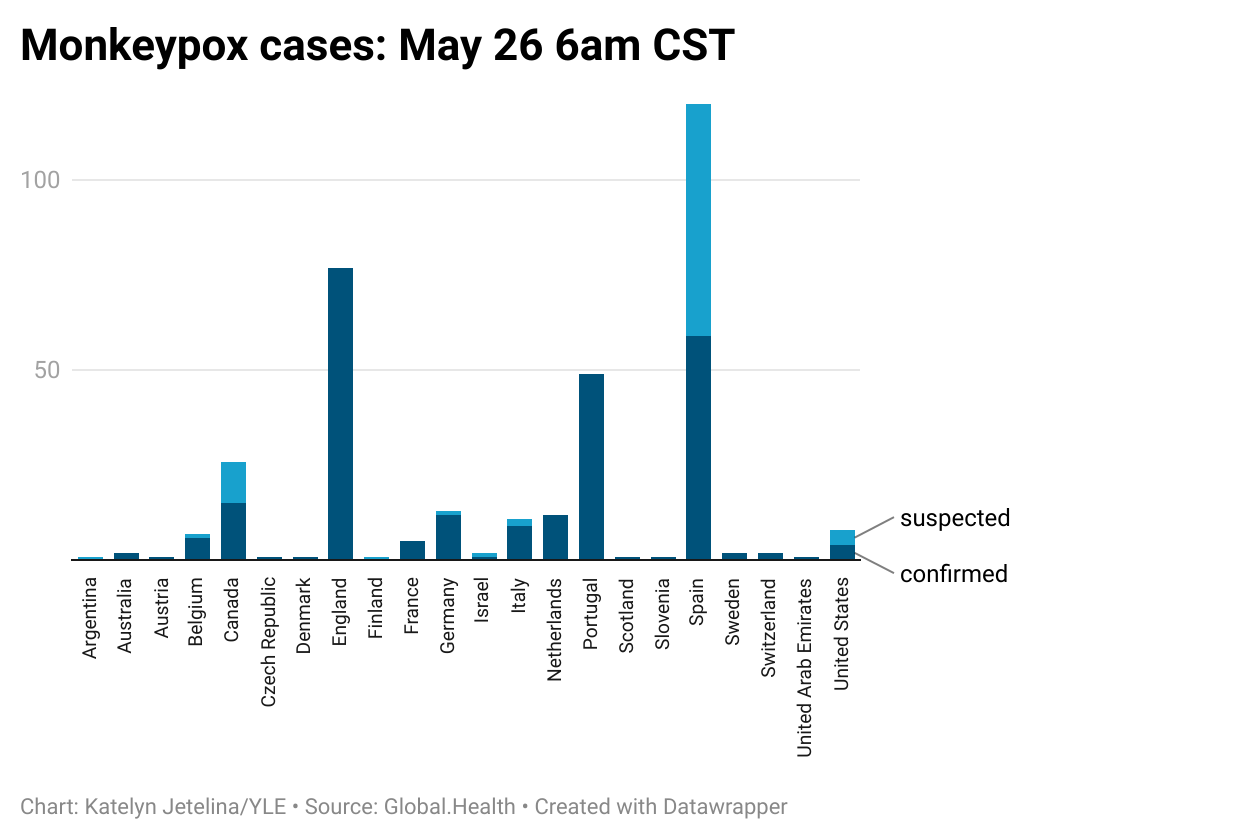

More MPX cases continue to be identified. Thanks to Global.Health scraping information from public sources, we have almost real-time epidemiological numbers to follow. As of this morning, 344 confirmed and suspected cases span 22 countries. The U.S. has reported 4 confirmed and 4 suspected cases.

It’s impossible to know how big this outbreak will be. The circulation of this disease is completely unique from previous outbreaks, and cases continue to lack defined chains of transmission. For example, cases continue to pop up with no history of travel, indicating sustained community transmission.

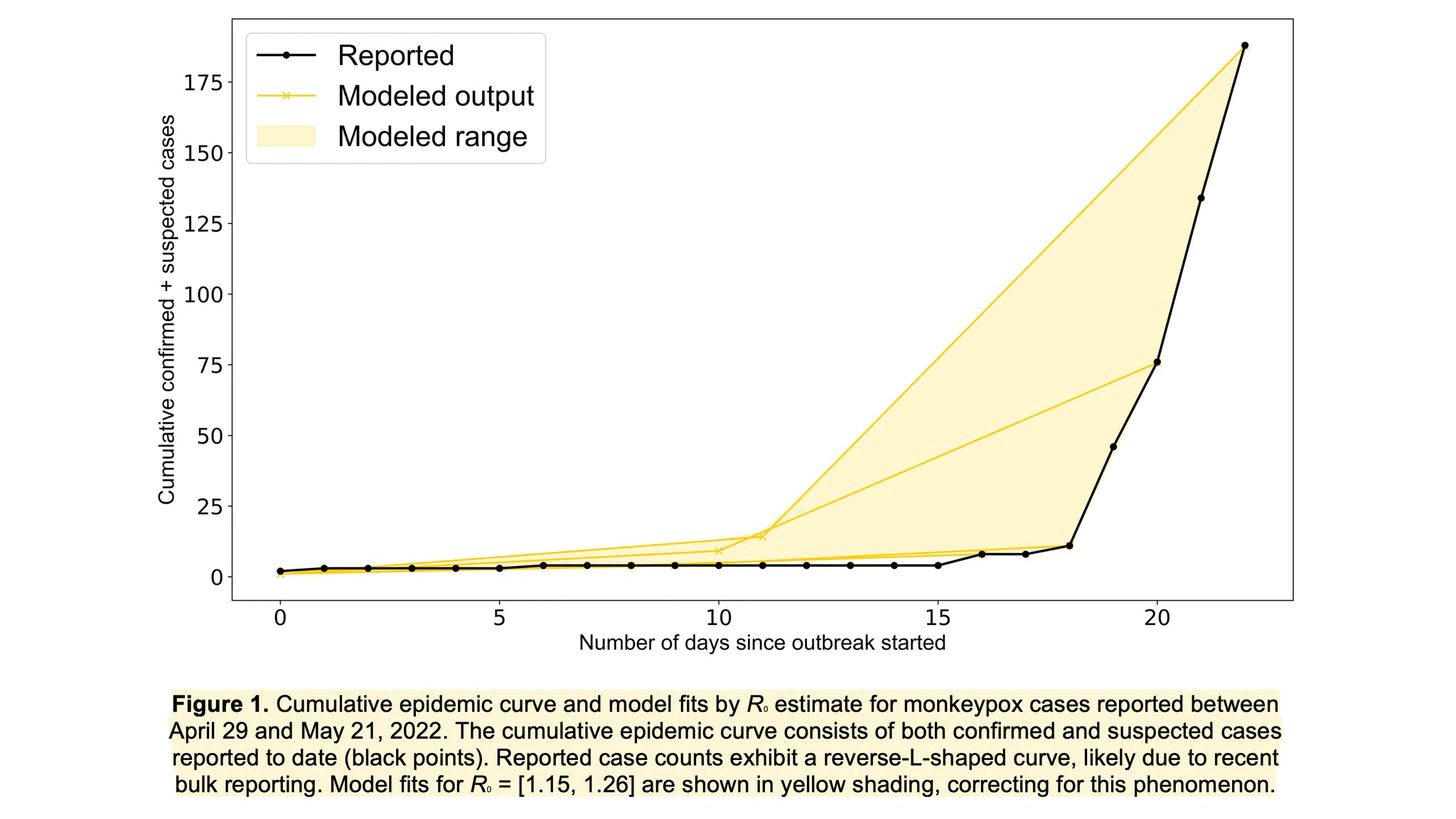

The rate of reported cases can be alarming. However, this is likely due to “bulk reporting,” which is very common with new outbreaks. As awareness increases, identification will also increase. This may also be due to MPX having a long incubation period (maximum 21 days from infection to symptoms), so MPX could have been under the radar for a while. As surveillance systems catch up, new case numbers will likely stabilize, too.

A group of American scientists provided an early estimate of R(0)—the average number of infections per confirmed infected person—of the current MPX outbreak. They found R(0) to range from 1.15 to 1.26. In other words, every infected person infects, on average, 1-2 others. This is pretty low and close to estimates from previous MPX outbreaks (1.46–2.67). (For reference, the R(0) of smallpox = 3 and Omicron =10). But, R(0) is difficult to estimate without good data, so as more cases accumulate we will eventually reach scientific consensus. If R(0) remains low, this means we can control the MPX outbreak by identifying cases early and intervening.

Contact Tracing and Risk Assessment

One of the best ways to understand a new outbreak (and associated risks) is to piece together contact tracing data. Publicly available information points to several amplifying events in Europe. Many cases have been connected to a festival in the Canary Islands between May 5 and May 15, which 80,000 people attended. Another cluster of cases is connected to a sauna in Spain and another cluster connected to a festival in Antwerp.

The majority of initial cases are among men who have sex with men (MSM). Given that sexual contact is, by definition, close contact, discerning whether spread is being driven by sex or other routes will be difficult to disentangle. Currently, scientists are testing whether live virus is present in semen and vaginal fluid. It will also be important to understand whether clinical presentation is atypical in these cases, too: Are lesions focused specifically in genital region? When is someone contagious? Is there asymptomatic transmission? Presymptaomtic? How long is infectious period? Papers will be coming out in the next few days that will shed light on these questions. Functionally, though, avoiding close contact with cases altogether is key. In addition, while first cases were detected among gay men, MPX is not a “gay disease.” This is critical because it’s easy to scapegoat groups in an association with a disease, which can lead to harassment, violence, stigma and discrimination. This would impede our efforts to identify cases, get them to care, and contain the outbreak.

Earlier this week, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control released a risk assessment report determining the overall risk is “moderate” for people having multiple sexual partners due to two factors:

High risk of further spread because of low rate of smallpox vaccination, signs of MPX transmission during sex (and thus close contact), and large gatherings coming.

Low risk of severe disease because the majority of cases thus far have been mild. Only about ~12% of cases are hospitalized. No deaths have been reported.

The report concluded the general public is at “low risk” as the probability of exposure is very low. While this is reassuring, we need to be careful with this language for a few reasons:

MPX is spread through many modes, like viral transmission on clothing or respiratory droplets during prolonged periods of contact. MPX is not a sexually transmitted disease. The public can’t lose sight of this, as we will likely see cases beyond interconnected sexual networks.

MPX is more severe for vulnerable populations, like young children, pregnant people, and immunosuppressed, or those who don’t seek care. So, while general risk is low, this won’t be the case if MPX starts infiltrating vulnerable pockets.

There are significant implications if the virus jumps from humans to animals. If the virus finds a new animal host, like squirrels, this disease could easily become endemic in other places around the world. (The transmission from humans to pet animals is theoretically possible.) We’ve seen reverse zoonosis is possible, like among mink farms and white tailed deer during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Genomic epidemiology

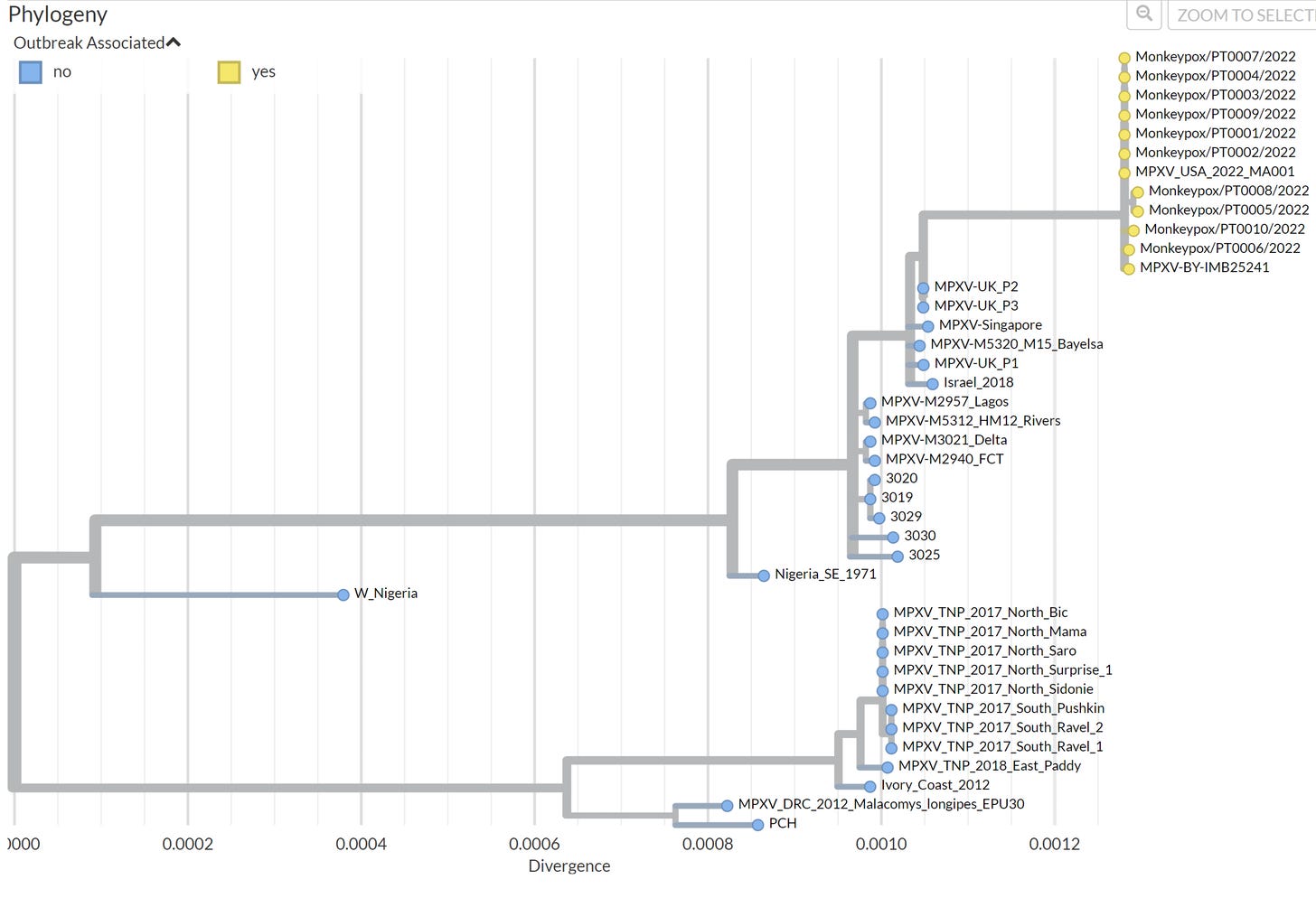

Impressively, 12 cases in the current outbreak have been genomically sequenced. This means samples were taken from the infected and the virus was mapped, compared to previous cases of MPX, and publicly shared in record time. This data is imperative, as it provides clues to some of our unanswered questions:

If, and how, has this virus mutated? So far, the closest ancestor is a MPX case sequenced from the U.K. in 2018, which was linked to travel to Nigeria. But it’s not identical. On average, the sequences have 50 alterations (called SNPS) compared to the 2018 sample. We expect viruses to mutate and change over time. But, DNA viruses (like MPX) mutate much slower than RNA viruses (like SARS-CoV-2) and 50 SNPS is higher than what we would expect.

Has the virus mutated to become more transmissible? There are some potentially interesting mutations. But figuring out the impact of these specific SNPS, or more importantly, the impact of the combination of changes will take time. This is even more difficult with MPX (compared to SARS-CoV-2, for example) because DNA genomes are far longer than RNA genomes, making the impact of mutations even harder to predict.

Did these mutations occur in a single round of replication or did it happen over time? Was this a single event or multiple events? One big mystery is how this MPX outbreak started. The closest case was sequenced more than 4 years ago, and a lot could have happened since then. All of the sequences are clustered very tightly together (see below). This means the cases are likely all from a single event (rather than having outbreaks in North America and Europe separate from each other, for example). This “event” could have been a common source in Nigeria and spreading silently for a while before being identified. The source is yet to be determined.

Ongoing discussions in the genomic surveillance community continue.

Bottom line

The MPX outbreak continues to unfold as more and more cases are identified and confirmed. It’s crucial that cases and contacts continue to come forward for treatment and quarantine without prejudice and stigma. Thanks to quickly shared genomic surveillance, we know the virus has changed since 2018, but we don’t know what it really means yet.

While we get answers, the best thing we can do is quickly identify cases (here are the signs and symptoms of MPX), inform close contacts, and contain the virus. This will force MPX to fizzle out as soon as possible and ensure no new animal reservoirs emerge.

Love, YLE and Dr. Anne Rimoin

Big thanks to Dr. Gregg Gonsalves, an epidemiologist at Yale and AIDS advocate for 30 years, who helped with language throughout.

Dr. Rimoin is a global leader in monkeypox and emerging diseases and Professor and Endowed Chair in Infectious Diseases and Public Health at UCLA. She is also the founder of the UCLA-DRC Health Research Training Program investigating emerging infections.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

Your work is critical as a non-biased, factual report that one can send to non-medical family and friends as a document one can Trust to be based on facts and analysis, not political bias. I forward your work to many. D. Murphy, MD. FAAP and trained in pediatric infectious disease .

MPX hasn’t bubbled to the top of most news cycles in the past few days, given the public health crises manifested in the latest school shooting. Viewing the world through an epidemiological lens, it is necessary to keep a lot of balls in the air. I appreciate this morning’s report.