This post contains information regarding the use of animals for scientific discovery. If you would rather not read this part, skip the “effectiveness” section.

Two days ago the CDC activated an Emergency Operations Center for our monkeypox (MPX) response. This included a plan to broaden testing and eligibility for MPX vaccination. Now everyone who is presumed to have MPX exposure is eligible for a vaccine (not just those with a confirmed exposure). This opens up eligibility quite a bit.

This vaccine is not in our typical “repertoire,” so here is a rundown of the vaccine options, history, effectiveness, safety, and how we are using them…for now.

Old vaccine: ACAM2000

The first option is ACAM2000, which is the second generation of our old smallpox vaccine. Our original smallpox vaccine (called Dryvax) was licensed in 1931, but it had a questionable safety profile and used an outdated manufacturing technique. Dryvax was no longer manufactured when its updated clone, ACAM2000, was licensed in 2007. ACAM2000 is a single dose, and we have over 200 million doses stockpiled in the event of bioterrorism.

ACAM2000 is a “replication-competent vaccine,” which means it uses live, infectious virus. The vaccine does not contain variola (the virus that causes smallpox), so the vaccine cannot cause smallpox. Instead, it contains the vaccinia virus, which belongs to the smallpox family but causes milder disease. The vaccine is very effective. Because MPX is genetically so closely related to smallpox, we can use this vaccine for the current outbreak.

But this vaccine is rough for a few reasons:

Administration. It’s administered differently than the vaccines we’re used to. Instead of a single needle, it’s a two-pronged needle that’s dipped into vaccine solution, and the skin is pricked with drops of the vaccine. Then, the virus begins growing at the injection site causing a red, itchy sore spot within 3-4 days. The blister then dries up forming a scab that falls off around week 3. This leaves a small scar.

Side effects. Common side effects include itching, sore arm, fever, headache, body ache, mild rash, and fatigue. It can cause myocarditis and pericarditis (heart inflammation). Based on clinical studies, this occurs 1 in 175 adults who get the vaccine for the first time.

Transmission and high-risk groups. This vaccine contains live infectious virus. This means unvaccinated people can be accidentally infected by someone who recently received the vaccine. Taking special care of the vaccination site is required to prevent the virus from spreading. High-risk people (e.g., pregnant women, those who have heart, immune system, or skin problems) can have serious adverse events if they are vaccinated or infected through close contact with a person who was vaccinated.

As with every vaccine, we must weigh benefits with risks before administration of ACAM2000. The risks outweigh benefits for many groups right now. (This may change, for example, if there was a bioterrorism event with no other options).

New vaccine: Jynneos

A much newer vaccine, called Jynneos, is also available for adults aged 18+. It was licensed for use in 2019 and created by a company called Bavarian Nordic—a biotech company headquartered in Denmark. Jynneos is administered as a series of two injections (with the needles we are accustomed to), four weeks apart.

Jynneos is a weakened virus vaccine (called attenuated). Importantly, unlike ACAM2000, this vaccine is non-replicating. Other vaccines use this vaccine biotechnology platform, including chickenpox, MMR, and yellow fever vaccines.

Effectiveness

Approval of Jynneos was originally for smallpox and based on 22 clinical trials comprising a total of 7,800 participants aged 18 to 80 years old. Scientists tested the vaccine effectiveness on smallpox vaccine-naïve and smallpox vaccinated individuals. In the Phase 3 trials, neutralizing antibodies were compared among people who received Jynneos and those who received ACAM2000. Jynneos was highly effective.

To approve the vaccine for monkeypox, the FDA relied on survival data from non-human primate challenge studies. Primates were administered either the vaccine or a placebo and then 63 days later exposed to a lethal amount of virus. Survival ranged from 80% to 100% of vaccinated animals compared to 0% to 40% in the placebo group. Based on data from Africa, the CDC estimates the vaccine is 85% effective in preventing MPX among humans.

Safety

The safety profile was favorable in clinical trials among a diverse set of participants: smallpox vaccine-naïve healthy adults, healthy adults previously vaccinated with a smallpox vaccine, HIV-infected adults, and adults with eczema.

Side effects were about the same for dose 1 compared to dose 2. Adverse effects included:

Injection site reactions (pain, redness, swelling, induration, itching)

Muscle pain (43% in vaccinated vs. 17.6% in placebo)

Headache (35% vs. 26%)

Fatigue (30% vs. 21%)

Nausea (17% vs. 13%)

Chills (10% vs. 6%)

Serious adverse reactions were very rare (0.05%). Clinical trials paid particularly close attention to cardiac events given concerns with the old smallpox vaccine. Cardiac events were rarer with Jynneos. In the 22 clinical trials, two deaths were reported and were not related to the vaccine (one due to overdose and the second due to suicide).

Jynneos is certainly the preferred vaccine given it has fewer side effects. And this is the one being distributed in the U.S. However, we have a limited supply. To date, 9,000 doses of the vaccine have been given out for MPX, and 56,000 additional doses of Jynneos are available immediately. We ordered more vaccines, and 750,000 additional doses will be available this summer. By the end of the year, we should have a total of 1.6 million doses available for the public. It’s yet to be determined if this supply can keep up with demand.

Usage

The vaccines are effective at protecting people against monkeypox before exposure. However, it can also help prevent disease or make it less severe after exposure. The CDC recommends the vaccine be given within four days of exposure to prevent onset of the disease. It can be given after four days to reduce the symptoms.

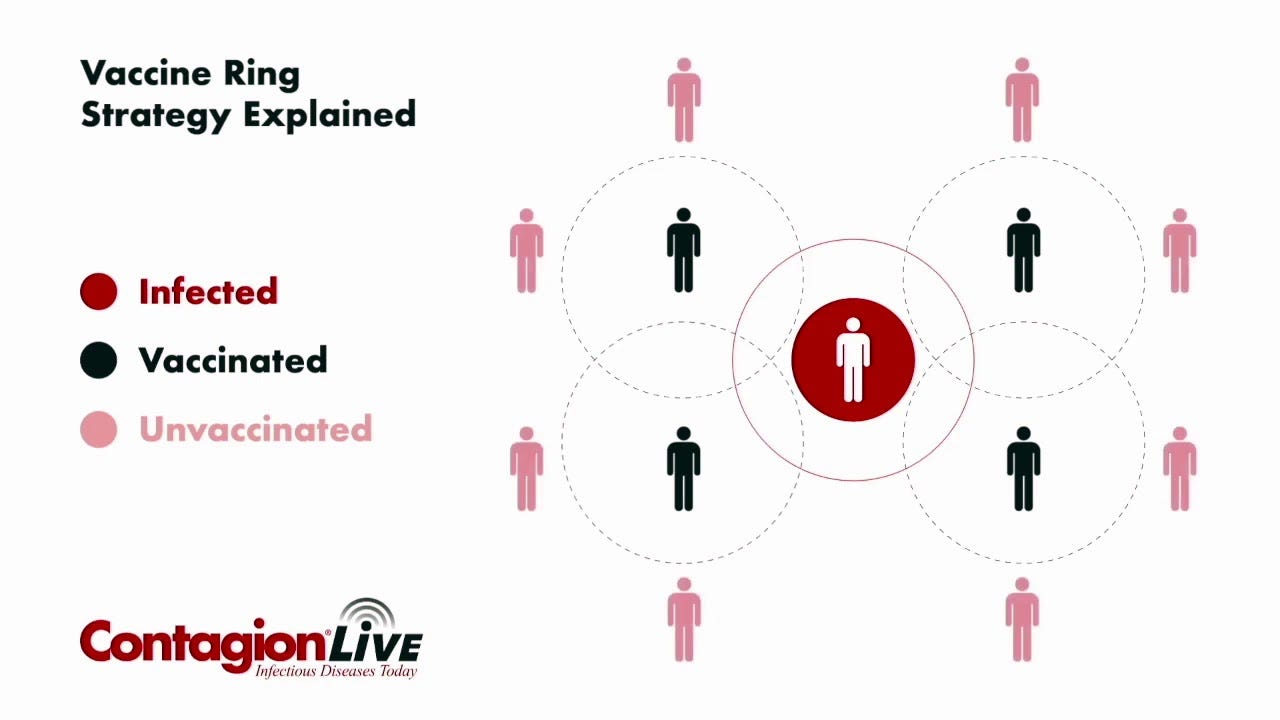

Our strategy on how to handle this limited supply of vaccines has shifted. In the beginning, we started off with a “ring vaccination” approach— vaccinate those directly exposed but also vaccinate others who are in close contact with that person, such as family and friends. This vaccine strategy helped eradicate smallpox. However, it relies heavily on quick identification of cases (meaning optimal education and testing) and effective contact tracing. We’re having trouble with both.

Now our strategy has shifted, as we may not be able to actively identify all contacts. So we are casting a wider net. For example, if someone attended a party or venue where monkeypox was known to spread, they are eligible even if they didn’t have a confirmed contact. This is a mass post-exposure strategy.

When our vaccine supply increases, we can move to a pre-exposure strategy. It’s not clear whether we will (or will not) need this, as we have to see how the epidemic unfolds. It’s also not clear what will happen if children less than 18 years old will need to be vaccinated (as the vaccines are currently not approved for them).

We also need to be sure countries with the more severe MPX strain, like Cameroon and Nigeria, have access to vaccines first. It’s not entirely clear that this is happening. Equitable distribution is where the WHO declaring a PHEIC would (theoretically) help a lot. (By the way, PHEIC is already reconvening with the news of the outbreak spilling over into more vulnerable populations, like children.)

Bottom line

We have two vaccine options in the U.S., with one more favorable than the other. Jynneos is safe and effective. If you’re eligible, go get a vaccine. Vaccines will help control this epidemic, but we need to do the ground work: educate, answer questions, reduce stigma, and improve access. We absolutely need to take this virus seriously so it doesn’t become endemic in more places around the world.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

What is the susceptibility to those who were vaccinated against smallpox in the 50s as children. Is there residual cross-protection decades later?

Greetings Dr. Jetelina,

Thank you for the clear and concise information on all of the subjects that you cover.

I am a 70 yo male that has been vaccinated for smallpox twice. Once as an adolescent and again in the early 70s in the military. My 70 yo wife has been vaccinated once as an adolescent.

Are those 'old' vaccinations effective against MPX?

Thanks again!