Si quiere leer la versión en español, pulse aquí.

It looks like Omicron has peaked in the United States and in many countries across the globe. Case patterns may uptick with the introduction of subvariant lineage, BA.2, but with a little luck we will largely be on our descent. And I can’t help but notice my inbox piled with great questions: Is this the end? What’s next? How do we prepare?

It’s taken me longer than I want to admit to gather my thoughts. These are warranted, simple, legitimate questions with very complex answers. So, for what it’s worth, here is my attempt…

Is this the end?

In order to know how this will end, we need to look at how other pandemics ended. First, recognize the last part of that sentence…pandemics end. Every epi curve comes down. This pandemic will end, too. Hold that fact close to you.

However, “pandemic ends” look and feel very different depending on the time period, the global response, the individual-level response, and the virus itself. Broadly “pandemic ends” can be placed into three categories:

Faded away. There have been several viruses that… faded away. An example of this was SARS. It started in 2002 and while it was mainly concentrated in Asia, it did spread across the world. A short 1.5 years later the SARS pandemic ended. The virus was stopped largely due to an effective, global public health response: Testing, isolating and quarantining, and restricting travel. These strategies were particularly effective because of the intrinsic properties of the virus: Symptomatic people spread SARS. So, if someone was sick, they knew it and isolated. This is unlike SARS-CoV-2 where we have many asymptomatic people spreading the virus. If the globe worked together, very early on, we could have eradicated SARS-CoV-2 through public health mitigation measures alone. But, this option has long gone.

Vaccines. We’ve stopped other viruses through universal vaccination. For example, in the mid 1940’s, polio killed ~60,000 people a year which equated to a case fatality rate of 15-30%. Then in 1955, a 90% effective vaccine was introduced and people lined up for the vaccine. This largely got polio under control and by 1979 it was eradicated in the United States. Polio is still around in small pockets around the world, but I’m optimistic it will be eradicated globally soon. Smallpox is also a textbook example of eradicating a virus through vaccination. It takes time though. And teamwork. If the globe works together, we could possibly eradicate SARS-CoV-2 with vaccines. (Now that we have numerous animal reservoirs, though, this is close to impossible).

Endemic. Other pandemics end by going into an endemic state, like the 1918 flu. During the first two years of the 1918 pandemic, case fatality rate ranged from 10-20% and caused more than 50 million deaths worldwide. Over time, the virus attenuated; it became less severe. Today we still have descendent strains of the 1918 flu floating around but the case fatality rate is ~0.1%. And, as a society, we’ve accepted this level of mortality (even though we don’t necessarily have to). Some have even used the flu as a benchmark during this pandemic to define “mild disease”.

The vast majority of scientists think an endemic state is the future of SARS-CoV-2. I agree. However, there are a number of misconceptions about what “endemic” means, making it the most misused word of the pandemic (after “herd immunity”). Just because endemic contains “end” doesn’t means this is the end. This isn’t game over; this doesn’t mean we will have zero cases; it doesn’t mean a flat horizontal line here on out. It also doesn’t mean there will be no harm and no death.

Instead, endemic means a “steady state”; static; no huge waves; no statewide crisis; no calls for help from physicians on the front line. Importantly, endemic does not mean no suffering. As Dr. Aris Katzourakis— evolutionary virologist— eloquently stated:

“A disease can be endemic and both widespread and deadly. Malaria killed more than 600,000 people in 2020. Ten million fell ill with tuberculosis that same year and 1.5 million died. Endemic certainly does not mean that evolution has somehow tamed a pathogen so that life simply returns to ‘normal’ (…) Nor does it suggest guaranteed stability: there can still be disruptive waves from endemic infections, as seen with the US measles outbreak in 2019.”

We are not in an endemic state right now with SARS-CoV-2. We are experiencing state-wide and nation-wide swings. The virus transmission is not stable. Our hospitals are overwhelmed. We’re seeing disruptions in almost every part of our society. But when we do reach an endemic state, there will be no declaration. There will be no “game over” front page headliner. It will happen slowly. And we won’t know it happened until it passed. So this leads everyone to the next question…

What’s next?

This virus will continue to jump from person-to-person and it will mutate. We may have another wave, but we may not. The presence, timing, and height of that wave are going to be dependent on a few things:

Omicron infection will help, but we don’t know for how long. By the end of February, Omicron will have touched 36-46% of Americans. This level of immunity, combined with vaccinations, will, no doubt, help build our immunity wall. While infection- or vaccine-acquired immunity isn’t perfect, it does help protect against severe disease by shortening the time of infection and reducing the amount of virus that replicates in the body.

But Omicron induces a very different disease pathway than previous variants. The timing and height of the next wave is partially dependent on the durability and strength of Omicron-induced immunity. How many people will actually mount strong protection from Omicron? How long will immunity last? Will it be shorter because Omicron was more mild? Or will it be about the same as before (median 16 months with large variability)?

The virus will mutate, but we don’t know how. Right now, SARS-CoV-2 is mutating every two weeks. And the virus will continue to mutate. Unfortunately, viruses don’t change to become less severe. It’s true that Omicron is less severe than Delta. And, it’s an obviously attractive scenario if this virus continues to mutate to be less and less severe. But it’s not guaranteed. That’s because mutations are random. There is no high-level thinking. The virus’s only goal is to survive and the only thing that keeps the virus surviving is transmission—the ability to continue to infect and jump from person-to-person. If the virus mutates to be more transmissible and it just happens to also make people very ill, that’s the version that will spread because the strategy is working.

There has to be a global response. If the pandemic has taught us nothing else, it’s that this globe is connected. What happens in Southern Africa (Omicron), the UK (Alpha), Colombia (Mu), United States (Iota), China (Wuhuan variant), impacts us. Our priority needs to be not only national domination of the virus, but also global domination of the virus.

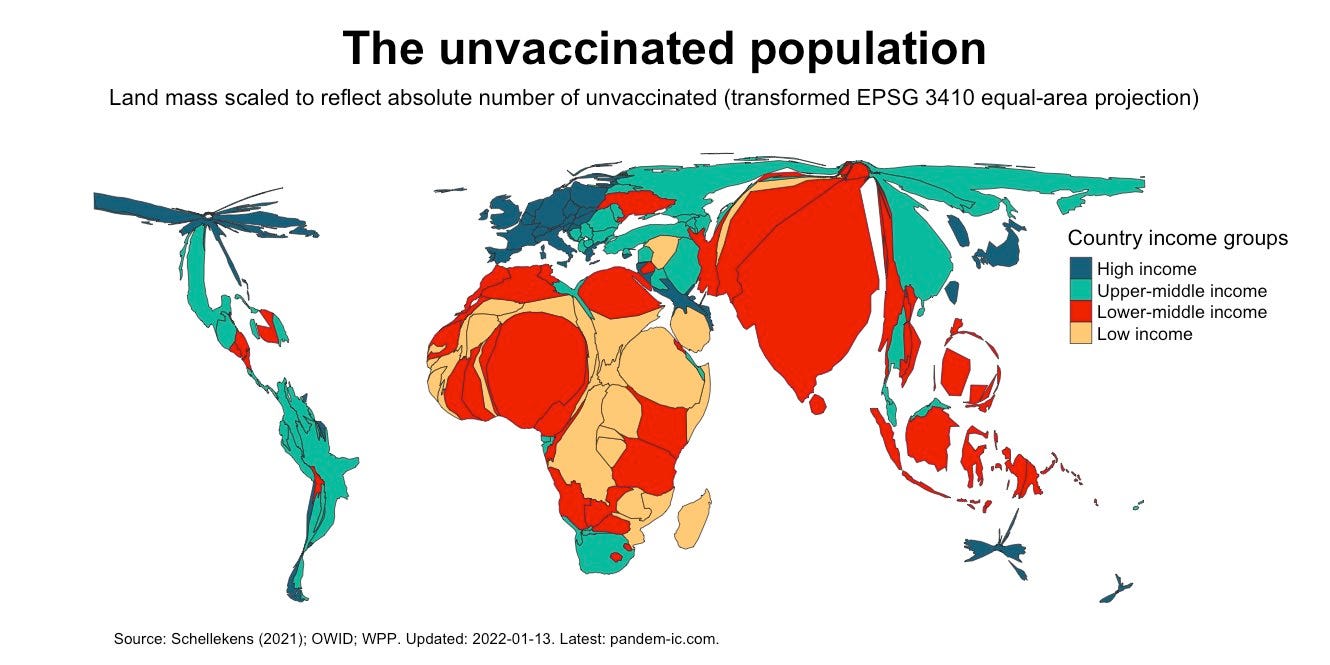

The best way to do this is to get vaccines to people who need them: The unvaccinated. Yes, focusing on when and how to boost is important, but not nearly as important as getting the unvaccinated vaccinated, which includes ~3 billion people. How do we do this? We share vaccine patents so other countries can manufacture and distribute the innovative biotechnology. This will improve reach. We also need to invest and create different types of vaccines. For example, Dr. Peter Hotez just created a non-profit, pediatric COVID19 vaccine—CORBEVAX— that uses old but proven vaccine technology that can be manufactured and distributed easier across the world.

And while supply and access to vaccines is incredibly important, it’s not the entire story. Mis- and dis-information campaigns have infiltrated trust in science and medicine across the world. For example, the vaccination rate is very low (30%) in South Africa, but not because of supply, instead people just don’t trust the vaccines. We need to work very hard to build trust in science on a global level.

So, the next wave will be dependent on infection-induced immunity, how this virus mutates, and how we respond as a global community. But, to some degree, it doesn’t matter…if we prepare.

How do we prepare?

We strengthen our tools. And we use them wisely.

Increase vaccine uptake. We can’t transmit a virus we don’t have. Vaccines reduce transmission in several ways. So, we increase our booster rate. Concurrently we define and recalibrate our national goals of the COVID-19 vaccines. Do we need an Omicron-specific vaccine? Probably not. But, how do predict what the next dose should look like? How do we better support next generation vaccines, like the pan-coronavirus super vaccine? We also decrease our unvaccinated rate by approaching hesitancy with empathy and open ears. But, we cannot have a “vaccine only” approach.

Continue to wear masks. Masks, on average, reduce transmission by 56%. This isn’t great, but it’s not nothing. If we upgrade to N95/KN94/KF94, we reduce transmission up to 95%. And, this includes kids in school. There is zero evidence that masks harm, physically or psychologically, kids. There is evidence, though, that masks reduce transmission among kids in school.

Invest in better filtration systems. HEPA filters reduce transmission by 65%. One HEPA filter equates to 2 windows open (2.5-fold decrease in transmission). This will undoubtedly help keep businesses, schools, childcares open if, and when, another variant arrives.

Scale up antigen testing. We need to empower people to break transmission chains. So, we need better access to tests. Four antigen tests per home free of charge was a great start. But we can’t stop there. There are blaring equity issues and we can do better. Once people get them, we need to let people use them. There is no reason an antigen test can’t be used for test-to-stay policies at schools and childcares. There’s no reason why a PCR must be used for clearance.

Increase supply of therapeutics. Therapeutics are a game changer for this pandemic. While they can’t prevent infection, they are very effective at preventing severe disease. They will alleviate stress on our health systems. The drug is going to change how we, as a society, look at disease— COVID19 will be treatable. By April we will have a million doses. By September, we will have 20 million doses. But is that enough supply? The federal government needs to take the risk and assume that it’s not enough. We shouldn’t just ramp up supply of the Pfizer pill (which has limitations), but also support other companies to test risky, innovative science. Antivirals are difficult to make, but our goal should be 2-4 more therapeutic options in 2022.

Strengthen surveillance: Much to my surprise, COVID19 metrics largely held up during the Omicron wave: test positivity rate was followed by case trends, which was followed by hospitalizations and deaths. The raw number of cases or tests are not to be trusted, but the pattern is still solid for surveillance. I suspect this will change with more and more antigen tests, though. This means we need to strengthen our surveillance system proactively. Develop a systematic, national reporting platform in which antigen test results can be documented. We should also implement wastewater surveillance. But, teams need to be created and supported across the nation to do this.

Communicate. We desperately need top down communication. The CDC needs to come out from hiding and let their experts talk. We need weekly updates. But, more than that, we need a plan. We need to develop and communicate offramps and goals. If public health officials don’t, then other people will. And, when we don’t like their plan, we have no right to complain.

We also need bottom up communication. People need their questions answered. But, more importantly, we need to hear their perspectives. Only a multidisciplinary approach will get us out of this pandemic. Different perspectives will offer innovative solutions.

We aren’t all going to agree and that’s okay. In fact, the push and pull is necessary to move forward. But we need to listen. Listen is different than hearing as it requires effort: active, intentional, and focused. This means opening hard-to-read Op Ed’s with a curious mind. This means digesting an opinion aired on a late night talk show. This means having empathetic conversations with unvaccinated people instead of dangerously suggesting to just withdraw care. For the other side, this means recognizing our reality and privilege is not everyone’s. In fact, it’s not even the majority. So, we need to listen to the perspectives of immunocompromised who are being left behind or those with long COVID. Or healthcare workers’ lives that continue to be forever changed. Or parents of unvaccinated kids under 5. Or families that have to decide between buying dinner or buying antigen tests. Or those around the globe without access to any vaccine. All of these groups are struggling right now because we all want this pandemic to be over too, but we aren’t collectively taking the necessary measures to actually end it.

If we can do all of the above, we then keep society open while slowing down mutations in an equitable and wise manner. On an individual-level, we pay attention to transmission on the ground. If transmission is high, tighten up behaviors: wear masks inside, consider cancelling big events, use antigen tests a lot, trust positives, and isolate. When we are at low transmission, loosen up restrictions: we eat inside restaurants, we take off our masks, we let our kids play at indoor trampoline parks. We ride the waves while, simultaneously, pushing towards an endemic state.

Bottom Line: There will be an end, it’s just not how you pictured it. The journey to reach stasis is dependent on the virus, our population-level policies, and our individual-level decisions. It will depend on how we prepare and if we do it wisely. Together this will determine how many more people die, how many people get long COVID, how long the journey takes, how many mutations we have, how many vaccine doses we need, and, importantly how we keep sane and united. Our road to an endemic state doesn’t have to be bumpy. Whatever that path is, though, we will get to the end eventually.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, professor, researcher, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she has a research lab and teaches graduate-level courses, but at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

I just want to say thank you.

It's good to have someone smart explain the big picture AND offer solutions to make things better going forward. This is a terrific post, thank you for your work!