School is starting. And, with it, the contentious debate on what schools should and should not do. While the pandemic ravages on, the landscape continues to morph, and because of that, every subsequent school year has looked very different (hopefully for the better).

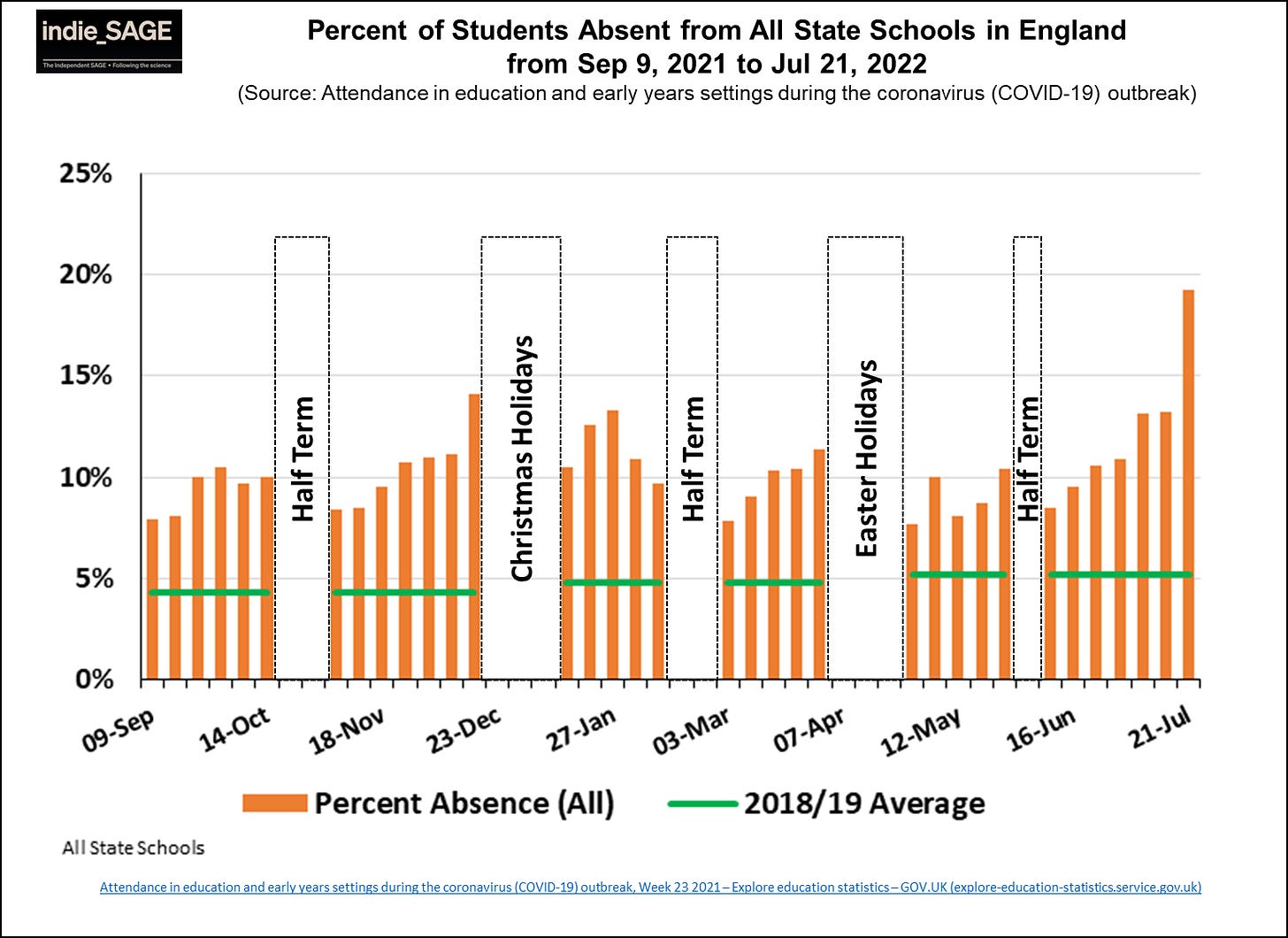

Unfortunately, student absences continue. As seen in London, students absences continue to be higher than before the pandemic. They were especially high at the end of this school year when BA.5 took hold. We know this is partially driven by reinfections, as children have the highest reinfection rate compared to any other age group.

It’s imperative that schools remain open, but they continue to seem stuck between “do everything” and “do nothing.” How many layers can a school feasibly implement given pandemic fatigue, limited resources, strong opinions, and differing risk calibrations?

The answer is multi-level; it requires a balance of tradeoffs from students, parents, teachers, schools, and the community. Our primary goal should be to maximize the number of days children are present. This can be accomplished many ways, but I think there are three buckets schools should really focus on.

Back-to-school vaccination campaign

We need strong, universal vaccine campaigns at schools. Parents report that schools, pediatricians, and health departments are the most trusted sources of information about vaccines. Schools can also significantly improve access to vaccines, as 38% of parents say they do not have enough info on where their kid can get vaccinated. A fall back-to-school campaign could really help move the needle for vaccinations, and thus school absences. And not just for COVID, but other vaccine preventable diseases.

COVID-19: The number of children vaccinated against COVID-19 remains abysmally low. (Only 10% of 5-11 year olds and 27% of 12-17 years olds are up to date.) Vaccines are safe, they prevent infections (especially within a few months of vaccination), prevent severe disease, and reduce risk of long COVID. But parents have a lot of great questions; we need to anticipate concerns.

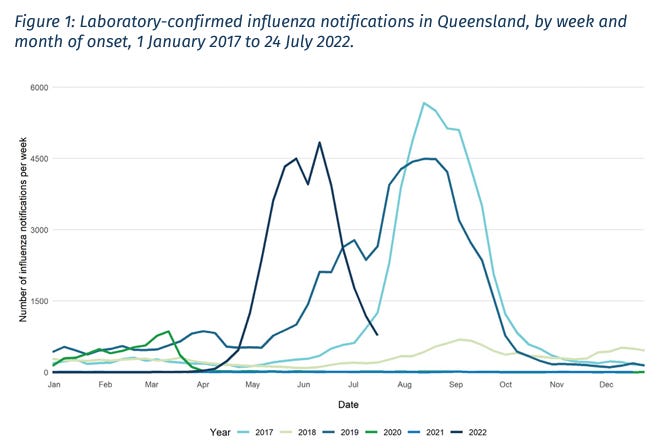

Flu. The flu season in Australia just wrapped up, and it wasn’t pretty. This is notable because, historically, Southern Hemisphere patterns predict what is to come in the Northern hemisphere. (We’ve been worried about a “twin-demic” since COVID-19 began, but it hasn’t happened yet. We are not sure why.) We should heed Australia’s warning and prepare for the worst.

Other routine vaccines. New York is strongly warning parents about a dip in routine vaccinations. For example, 13.8% of children have not been vaccinated against polio. This reflects patterns we’ve seen nationally and internationally with other routine vaccinations, too. We cannot lose decades-long progress towards eliminating vaccine-preventable diseases.

We can reimagine how vaccines and information reach students and parents. For example, the Teens for Vaccines campaign in Detroit was highly successful by empowering student ambassadors. A school district in Florida recognized that active communication and education promoted vaccine confidence and uptake, so they sent text reminders, posted on social media, and provided credible information. Los Angeles School District even had a TikTok campaign.

Ventilation and filtration

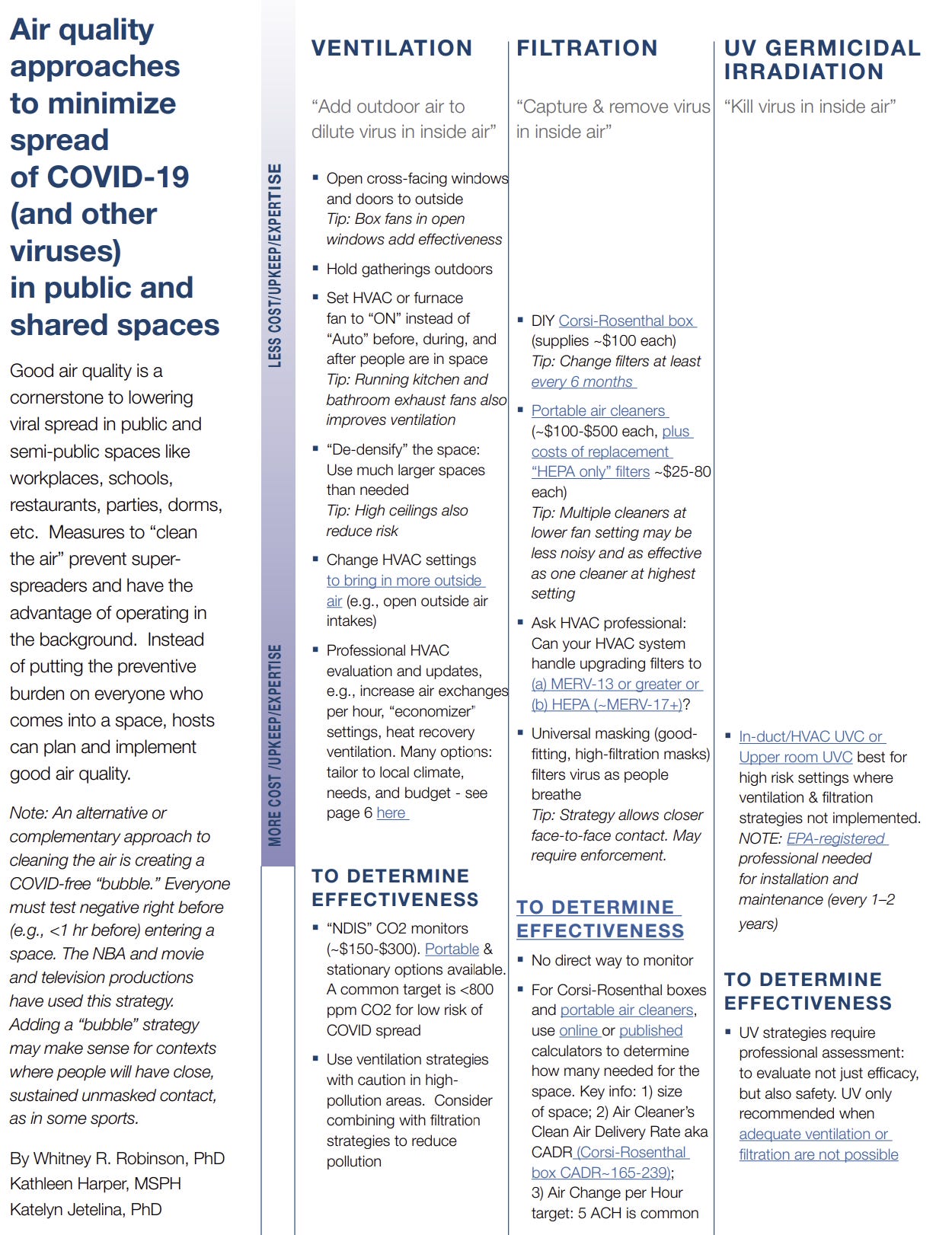

Schools need to upgrade their ventilation and filtration systems. This is one of the most powerful tools we have to curb COVID-19 and other viruses because it happens in the background—it’s an institutional-level intervention that doesn’t require the teachers, parents, or students to do anything. Unfortunately, a small proportion of schools report using these strategies, especially in rural and mid-poverty schools. Many administrators aren’t aware that federal funding is available for ventilation improvements.

Layman wording on how to improve ventilation and filtration is difficult to find. I worked with Dr. Whitney Robinson and Katie Harper, fellow epidemiologists, on a one pager that outlines available strategies and how to test effectiveness. This may help.

Testing and isolating

Now that everyone is eligible for vaccines, and treatments (monoclonal antibodies, antivirals and Evusheild) are available for high risk family members, a more targeted approach to testing, isolating, and masking in the upcoming school year is reasonable:

Testing. Sick, symptomatic kids should stay home. At-home or at-school antigen tests would be a great tool to use for this. (Do not use PCR tests, as these could stay positive for weeks).

Quarantining. Attending school far outweighs benefits of quarantining for a respiratory virus that is out of control in the community. It’s reasonable (and overdue) to remove quarantine requirements.

Isolation. The ideal scenario is that a child tests-to-exit isolation using antigen tests. But this can mean a lot of school missed (and a lot of work missed for parents), with the average infection lasting 8-10 days. The CDC says people can leave isolation after 5 days if they remain positive as long as they mask. If children need to go back to school at that time, it’s certainly reasonable and should be expected that kids mask if they are still positive.

Masks. Masks are effective to the wearer. They are even more effective if everyone is masking. If a school is in an area of high transmission, it’s certainly reasonable to mask to reduce transmission and, thus, reduce missing school. However, for that strategy to work, the wearer must mask everywhere else in the community. I don’t think it makes sense for a school to mandate masks if the larger community does not do so either. We shouldn’t ask students to hold down the fort if the larger community hasn’t also committed either.

Other random thoughts

Preparedness needs to be the name of the game. Schools need a plan in case we do get another Omicron-like event or if there’s is a big superspreader event, like a homecoming dance. There need to be very important conversations about normalizing decisions around masking, even if not required. Very important conversations may also need to ensue if a child is high risk in a classroom, so they, too, can attend in person learning.

Bottom line

This pandemic landscape continues to change and, with it, we should adapt. But if we continue to fail to act, children will continue to have their education disrupted by COVID19. There are a number of measures schools can put in place to maximize the number of days children are in school so they can have a safe and successful school year.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, biostatistician, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank, and at night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support the effort, please subscribe here:

I strongly disagree with the idea that masks shouldn’t be required in schools if they’re not required elsewhere in the community. Children have to go to school, so given that masks are most effective when everyone is wearing them, I’d feel much better about my child’s chances of not getting COVID in school if everyone were masked, even if masks aren’t required elsewhere in the community. True, it wouldn’t make sense for me to send my child in a mask, and then have him hang out maskless at a crowded arcade, but I can choose not to bring him to the arcade. I can’t choose not to bring him to school (unless I homeschool). There may be other reasons not to require masks in schools, but not having masking elsewhere in the community doesn’t seem to be one of them.

Can we talk about the fact that for the third year in a row the CDC is not releasing return to school guidance until after most of the schools in the south have already started (including in their home base of Atlanta!)? How do they expect to have any influence when schools had to come up with their COVID policies by early July to be ready for the August start date? Just frustrates me as a Houston pediatrician. We don't all live in the Northeast!