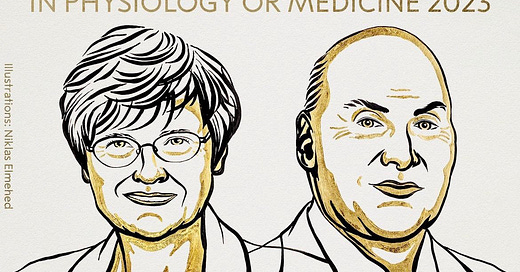

Yesterday, the 2023 Nobel Prize Winners for Physiology or Medicine went to Drew Weissman and Katalin Karikó for their discoveries in the biotechnology behind our Covid-19 mRNA vaccines.

Behind the amazing story of perseverance and collaborative spirit (it’s a fascinating story) is an absolutely revolutionary scientific discovery.

Here is the problem they solved, how we leveraged it for the pandemic, and the far-reaching implications.

The problem

In 1961, we discovered RNA in living things. RNA is a string of letters that gives our cells instructions on how to function.

At first, scientists explored how synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) could be leveraged in gene therapy. This was attractive because it meant we didn’t actually have to change our DNA. There would be no risk of accidentally introducing mutations that could affect how healthy genes work or, worst case, cause cancer.

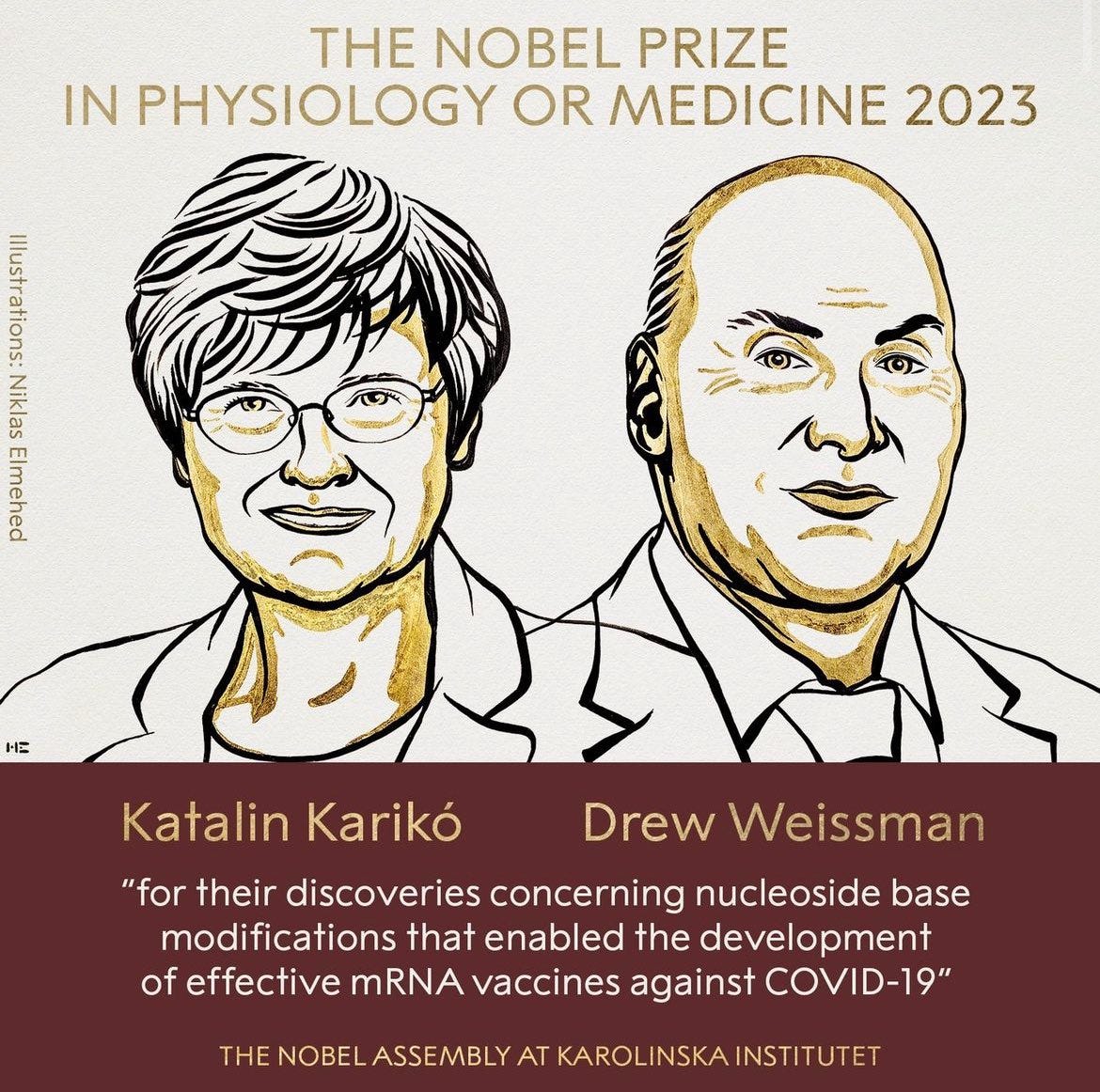

But, every time mRNA was introduced to cells for gene replacement, it caused a profound immune response. In other words, our immune system was doing its job: recognizing a foreign agent and trying to get rid of it.

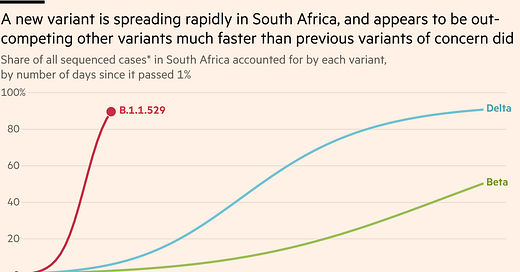

This caused scientists to pivot as there is an obvious application for a situation where you want an immune response: vaccination. In 1993, an mRNA influenza test showed successful induction of anti-influenza T cells in mice. This was incredibly exciting.

But there was a major challenge: the mRNA vaccines activated the immune system too early. This resulted in a mediocre antibody response and diverted T cells from a pathway that supported antibody production.

The solution

Enter Karikó, an RNA biochemist, and Weismann, an immunologist.

Karikó was confident she could fashion a vaccine from mRNA but encountered the same stubborn problem: the mice had trouble coping with the immune response after the mRNA vaccine. The quality of the immune response wasn’t as good as she’d hoped for either. Why did Karikó’s synthetic RNA do this when our cells constantly made mRNA with no such problem? Karikó’s RNA had to differ from the RNA our cells made, but how?

In 2005, Karikó and Weissman found the secret sauce: a group of RNA letter changes (i.e. modifications). A particular modification stood out: the change of U (uridine) to Ψ (pseudouridine, a common modification in our own RNA) prevented the immune system from recognizing the mRNA as foreign. They published these findings in Immunity, one of the top journals in the field of immunology.

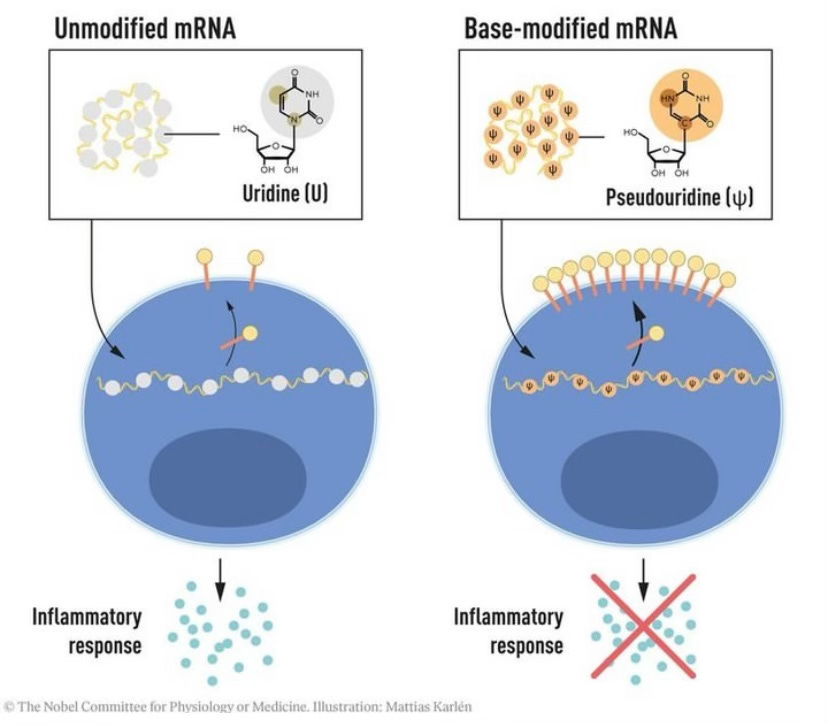

As the 2010s progressed, mRNA vaccines trickled into early-phase clinical trials. However, another matter still limited confidence in the approach: mRNA is so fragile that it is very difficult to work with and requires very cold storage conditions.

The pandemic

Then the pandemic came. While we had a key puzzle piece above, there were also other things that needed to come together:

Carrier: Needed to find an efficient way to deliver the mRNA to our cells before it degraded (we used fat bubbles, which also had a long history; see timeline above).

Cell instructions: Needed to stabilize the SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen.

Storage: Needed to supply special freezers to store the vaccine.

All of these were accomplished; the perfect storm that brought together scientific discovery, extensive investment, and global teamwork.

The implications

It is not an understatement to say that their discovery totally transformed our approach to vaccines. You would have a hard time naming a virus of public health importance for which an mRNA vaccine isn’t being attempted, but there are uses beyond that:

Vaccines against tick-borne infections that target proteins in tick saliva.

Vaccines to stop or reduce autoimmune diseases, like multiple sclerosis.

Bottom line

Your mRNA Covid-19 vaccine is Nobel Prize-worthy. And an excellent example of our gains from the decades-long road of scientific discovery.

Congratulations to Karikó and Weissman! Their work has saved millions of lives already and will continue to save millions more in the decades to come.

Love, YLE and EN

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Quite serendipitously Dr. Kariko’s memoir is coming out next week. I had the honor of reviewing the manuscript and it is incredible. The book is called Breaking Through: My Life in Science and it hits the shelves Oct 10.

Once again, a very clear and simple explanation. Thanks! And congratulations to Katalin and Drew! At last the Nobel Committee got out of the ice and awarded these two in record time. Well done.