Trust in public health is eroding, and the implications are far reaching. We, as a field, have to fix this.

Over the weekend

Any forward-facing scientist can tell you that receiving dangerous messages has been a common occurrence throughout the pandemic. But the hate, resentment, frustration, and anger was crystallized in one instance over the weekend: Elon Musk—the world’s richest man and new owner of Twitter—wrote the post below.

Five words, that were wrong on so many levels, garnered more than 1.17 million “likes,” 177,000 retweets, and international attention in mass media. Anyone who dared to disagree received a wave of truly grotesque comments. Even Musk noticed as he followed up on his original tweet with: “Truth resonates…”

Of course, the viral reaction is due to many things: social media algorithms, a polarized country, politics, misinformation, disinformation, opinions about Twitter, opinions about Elon. I also think Musk is trying to deflect negative attention from himself. It’s also a reflection of humans’ difficulty coping with randomness—people need someone to blame for the pandemic, the fear they experienced, the people they lost, or the jobs and livelihoods that were changed. The viral reaction was also an indication that people finally felt heard.

But all of the above also overlap with public health. And, their accumulation has been funneled into one sentiment towards our field: distrust.

Change in trust

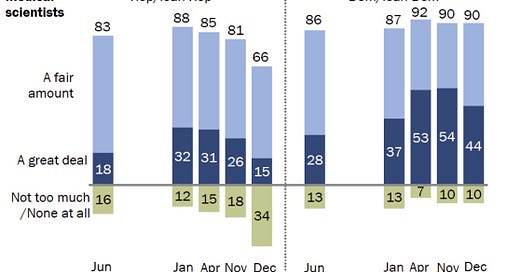

Every year, the Pew Research Center conducts a survey with Americans on public confidence in certain groups. Overall, trust in scientists has decreased throughout the pandemic, but ever so slightly. Interestingly it remained higher than public confidence in business officials, the military, public school principals, religious leaders, police officers, and elected officials.

If we compare the responses based on political affiliation, though, the story becomes jarring: confidence in scientists among Republicans dropped significantly. In fact, 1 in 3 Republicans have no confidence at all.

Furthermore, declines in trust in science were most pronounced among White adults. Americans with higher levels of education expressed more positive views of scientists than those with lower levels of education.

This is a huge problem, as trust equals lives

An Oxford report continually assesses country-level factors that most strongly predict COVID-19 deaths. The answer? Not pandemic preparedness. Not government. It was interpersonal trust—a measure of how much people think they can trust another citizen who they don’t already know. In other words, public health worked better in high-trust countries.

We cannot have one group trust public health and another not. This is not how viruses work. Infectious diseases violate the assumption of independence—what one person does directly impacts the person next to them. This is unlike cancer or diabetes, for example. Everyone has to be against a virus, or the virus thrives.

Perhaps most concerning is that this isn’t going to be our last pandemic. Since the 1918 flu, we’ve seen diseases emerge faster and faster. Public health also touches on our daily lives beyond infectious diseases: what we eat, social problems, gun violence, and all other acute and chronic medical problems. We need the trust of the community to move the needle for any of these.

What to do?

As the field of public health copes, self-reflects, and digests the past three years and weighs how to build for a better future, we have to make it our goal, our opportunity, to improve trust. As one scientist said, “You earn public confidence in small drops and you [lose] it in buckets.”

Bottom-up engagement is absolutely necessary. We need to enter conversations with humility. A conversation about false dichotomies (lock down vs. throwing caution to the wind) is necessary. A conversation about disease vs. the needs of a community is necessary. An honest conversation on what we (CDC, state epi, local epi, leaders, communicators) got wrong, got right, and why.

What does this look like? I have a few ideas:

Listening sessions. Not hearing and not telling, but listening to people and trusted messengers who are not in “our world.” Bringing them into the solution. It will be painful. It will be time consuming. But it has to be done.

A COVID-19 commission that is congressionally mandated, like the 9/11 commission. There is text in the PREVENT Act, but it’s not clear if PREVENT will pass.

Preparation for the future. Putting communication at the center of pandemic preparedness. This is still not being done. Building capacity for effective scientific communication needs to be a core of our national strategy. As I’ve written before, a lot needs to be done in this area.

I’m sure there are more and even better ways. And I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments. But the fact of the matter is there is no one solution. And this is going to take a whole lot of time.

Bottom line

We need to understand why five words in a Tweet carry so much weight in public health and threaten our entire profession. Will trust in science survive the pandemic? Maybe. It depends on what we, as a field, do next. If we don’t win hearts and minds, we won’t win against this virus or the next. Trust is key in public health. Our scientific work depends on it. Our health depends on it. Our lives depend on it. Now everyone needs to act like it. That includes, you, Mr. Musk.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Communication is so vital. Science and tech types often think they know everything, including how to communicate so the message is heard by all sorts of audiences. They don’t. (English major married to a mechanical engineering major for over 30 years, plus I spent my career writing tech manuals.) The medical community needs to decide what message they want to send, then let people trained in communications do the talking. For me, the messaging throughout the pandemic (but especially in the beginning) was severely lacking in cohesiveness and anticipating what different audiences might ask. Even now, many people believe the vaccines were created “overnight,” because the message that the technology had been developed over the last decade wasn’t communicated. Compare it to something the average person can understand, e.g “it’s still a car, but we tweaked the styling.” The messaging on masks was doomed when the first direction on masking was that it “wasn’t necessary.” People are left wondering who and what to trust when messaging keeps changing, and they found stability with the outliers who clung to incorrect information no matter what.

I appreciate what you are trying to do here. I do. But as a medical student of the early 2000s we were also told that no one should be in pain, treat pain aggressively and if we don’t we are bad doctors. People cannot become addicted if they have true pain. There were “studies” to back this up… We have to continue to question the motives and the policies of our government and our public health system. If we do not, people die. We have an ongoing opioid epidemic to prove this.

Let us not forget that the cdc originally told the public that masks were not necessary. This was not true, doctors knew this. But we needed to say this to prevent panic and preserve PPE for the medical community. Was that the right move? What if instead they came out and said we need to treat this like a war-time emergency? We need all people who have masks to drop them off so that the medical community can go to war against this virus.

So now everyone is questioning Fauci. He will be the scapegoat for the science community. I stand behind him as a physician having to make extremely difficult decisions to protect the lives of many. No question. That is what doctors do. But at the same time, the cdc is also telling people to believe that a a specific type of virus naturally appeared in one of the only cities in the entire world that happens to study these exact viruses. When you hear the sound of hooves…. This is no zebra.

If we don’t question it, we cannot make policies that will truly protect the public. If we cannot admit when we made a mistake, more people will die.