The Dose (October 18)

Where is RSV? Plus, Listeria detected in ready-to-eat meat, H5N1 in California, and a pesticide question.

This week’s Dose is a bit shorter, both because I’m running out of time and because there isn’t too much going on in the world of public health that may impact you (other than an election).

Let’s dig in!

Your “weather” report for the week

Covid-19, flu, and RSV are all at low levels. Enjoy the lull!

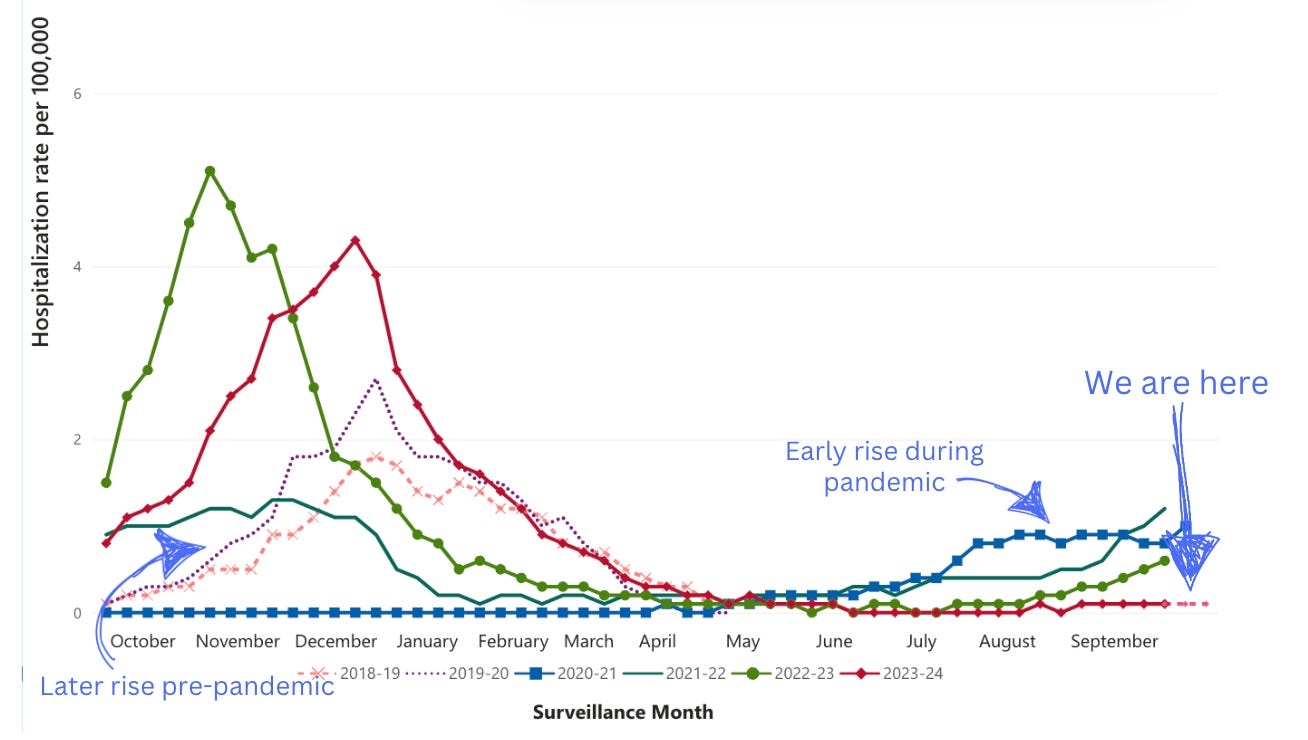

Where is RSV? If it were the past few years, RSV activity would already be increasing. Interestingly, RSV activity is still low. This means it is likely returning to pre-pandemic patterns.

It’s doing this in two ways:

Timing: During the pandemic, RSV started peaking in October and November. Last year, it started increasing at this time but peaked in mid-December. This year, it hasn’t even started increasing, which is typical of pre-pandemic patterns.

Peak: During the height of the pandemic, there was almost no RSV, thanks to non-pharmaceutical interventions like staying home. RSV came back with a vengeance in 2022 for two reasons:

Immunity debt: More people got RSV because people didn’t get RSV the two years before, so on a population level, more people got sick.

More testing: An interesting study showed RSV testing has increased. This may be due to increased awareness of infectious diseases during the pandemic.

Regardless, this is a great time to get your fall vaccines. Go here to search for a place near you.

Good news (in bad circumstances)

The polio campaign—now in second doses of vaccination—concluded in Central Gaza yesterday, with 181,429 children being vaccinated. In addition, 148,064 children received vitamin A supplements to help boost their immunity overall from malnutrition. Today, the second dose vaccination campaign is starting in southern Gaza.

This follows the first dose vaccination campaign 4 weeks ago, in which more than 500,000 (or 95% of eligible children) received a dose. This second dose is important to help stop polio transmission.

Listeria food recall

Listeria—a potentially dangerous bacteria—was detected during routine testing of finished products at one plant in Oregon. This has prompted the USDA to recall more than 11.7 million pounds of ready-to-eat meat. There aren’t any human illness cases yet. However, a Listeria detection automatically prompts a recall from USDA. (There is a huge debate on the effectiveness of a zero-tolerance policy; we can get into that another time.)

The intended call to action is to commerce and businesses: Remove products from circulation, including schools, restaurants, or grocery stores. (Here is a preliminary list of schools that received products.) In other words, it’s not worth a phone call to grandma (or a friend who is pregnant or people with weakened immune systems—the groups at highest risk for severe illness from Listeria) just yet.

For those wanting to take a more precautionary approach, USDA has a 345-page list of products recalled HERE. It’s hard to sift through, so use the “search” function. (Don’t we now have AI for this sort of stuff?)

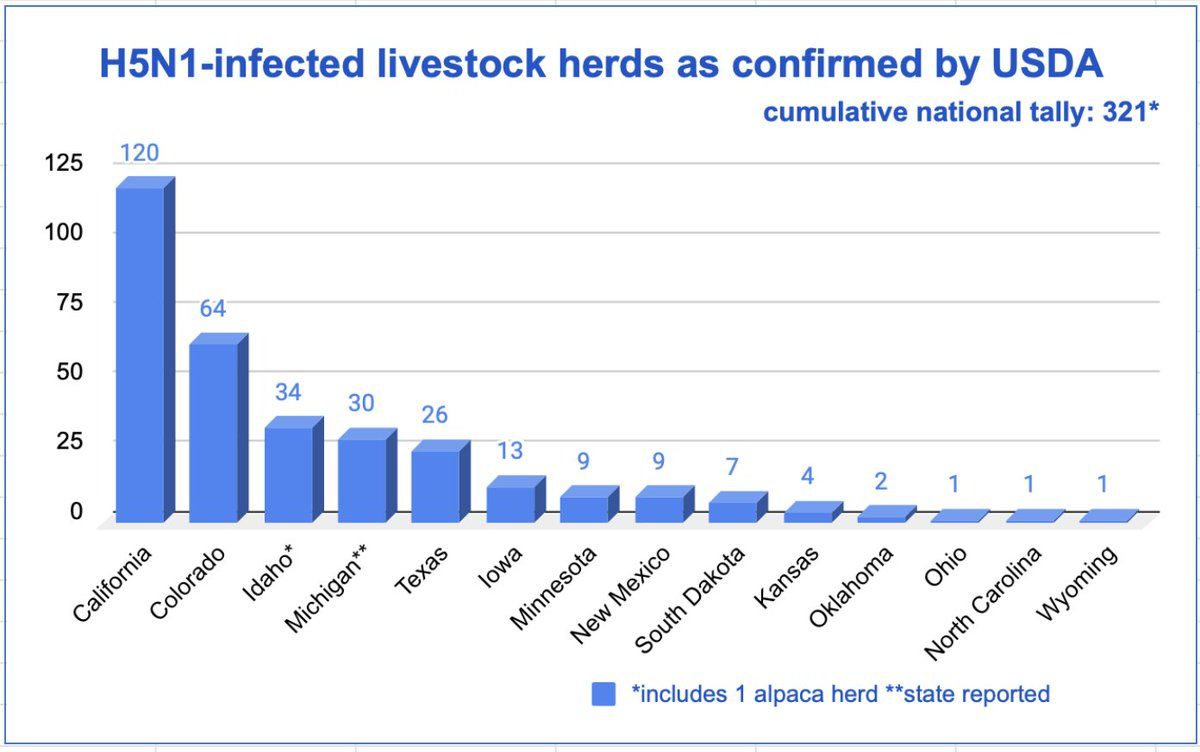

H5N1 exploding in California

The risk of H5N1 to the general public remains very low, so this update is only for awareness.

Bird flu—also known as H5N1—continues to spread like wildfire, infecting more dairy cow herds and workers. This is making people in public health nervous because we are going into flu season. If a worker, for example, has flu and then gets infected with H5N1, the two viruses can swap genes, significantly raising the risk of a flu pandemic.

Right now, all eyes are on California. In just a few weeks, CA has detected 120 infected dairy herds and 11 infected workers, which confirms that H5N1 is an occupational hazard.

CA leading the numbers in this outbreak shouldn’t be too surprising, though:

California is the #1 dairy producer in the United States, with over 1.7 million dairy cows. This means a higher probability of infected herds and infected workers. If we normalize by number of dairy cows across states, CA is not an outlier in human cases:

California: 0.64 worker infections per 100,000 dairy cows

Michigan: 0.45 per 100,000 dairy cows

Colorado: 0.5 per 100,000 dairy cows

Robust response. Because public health is decentralized, states are in the driver’s seat. Infrastructure, financial support, and leadership on a state level make a huge difference in public health; we can see it in state-to-state comparisons of responses to threats like H5N1. In other words, California is actively looking for H5N1, and it’s reflected in the numbers.

Reader Question Bag

Thank you for your great feedback and questions on the “Make America Healthy Again?” post. One reader asked: “Almost totally agree [with the YLE post]—except; does washing with water really remove pesticide residue? I mean, aren’t they mostly hydrophobic?”

A great question!

Studies show that washing produce with water can reduce pesticide residue levels by about 40-77%. There are two reasons for this large range:

Some pesticides are hydrophobic—they have a protective bubble around them, so water cannot penetrate and break them up.

Fruits and vegetables’ surfaces matter. Washing fruits and vegetables with smoother skins, like apples and tomatoes, is particularly effective.

Regardless, for hydrophobic pesticides or produce with rougher surfaces, rubbing or scrubbing the produce under running water helps physically dislodge and reduce pesticide residues on the surface (—or peeling, of course).

Bottom line

You are all caught up with public health this week! See you next week.

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. The main goal of this newsletter is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Every time I read these I'm just so grateful for your and your colleagues' work!

Thank you for sharing important info. In order to avoid muddying an issue, perhaps there's another term to use for clarity, like immunity gap or something that removes the word immunity altogether, since that's not really the process? Thanks for your diligent work.

https://healthjournalism.org/blog/2022/12/why-using-the-term-immunity-debt-is-problematic-for-reporters/