It’s officially wildfire season. Climate change has made wildfires more frequent and intense. We certainly don’t need to inform people in Canada and the Northeast, as they can just look outside and see dangerous levels of smoke.

Wildfire smoke contains tiny particles <2.5 microns in diameter (PM2.5) that can enter the lungs and irritate our respiratory linings.

A limited number of epidemiological studies have evaluated the cumulative effects of breathing in wildfire smoke, but most studies have been among firefighters. One scientific review found exposure to wildfire smoke over multiple days has an impact on lung function and heart problems. However, it’s unclear if and how these results translate to the general population.

Regardless, more caution is warranted the longer you’re exposed to smoke and the more dense the smoke. Symptoms can range from mild (e.g., eye irritation) to serious health impacts (e.g., exacerbation of asthma). Particularly high-risk groups include the following:

Older adults

Pregnant people

Children

People with preexisting respiratory and heart conditions

There is a lot you can do

CDC suggests multiple ways for reducing your exposure. These include:

Stay indoors, if possible.

Keep your indoor air as clean as possible. Run an air conditioner if you have one, but keep the fresh-air intake closed.

Use an air filter. Use a freestanding indoor air filter with particle removal.

Do not add to indoor pollution. Do not use candles, fireplaces, or smoke tobacco. Do not vacuum because it stirs up particles inside your home.

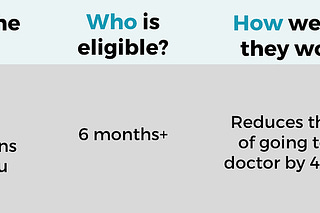

Wear an N95 outside. Recent research found that N95s reduced hospitalizations from wildfire smoke by 30%. In other words, it offers some protection, at least in the short term while running to the grocery store, for example. Cloth, paper masks, and tissues will not filter out the smoke.

Bottom line

Stay safe out there!

Love, YLE

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

I'm in Philly, where it smells like a campfire, and looks like a bad glam rock concert full of fake smoke and orange light.

I was swimming outdoors last night before this got worse (PM 2.5 was maybe 130 at the time?) and found myself wheezing, which is not something I've ever felt before outside of infections. Covid test negative, of course, ha! I thought the splashing around of water might help a little with the particulates just above the water surface... not much obviously.

Currently I don't smell smoke when I wear an N95 outside. It absolutely does help, since N/KN95's are designed to filter out 95% of particles 0.3 microns or larger. Better to stay inside and do the other behaviors Dr. Jetelina recommends.

PM 2.5 just hit 279 here. I have such a new appreciation for New Delhi, Shanghai, Mumbai, etc. So awful to live in this sort of poisoned air.

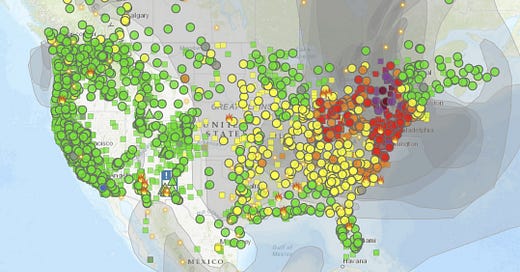

The best map of this, with a forecast, may be the one at https://firesmoke.ca/forecasts/current/