Florida’s recommendations give room for measles to spread

A slippery road we cannot go down

The measles outbreak at a Florida elementary school has grown to 8 cases and counting.

We have measles outbreaks all the time (although the rate is increasing due to vaccine hesitancy), but this one came with a new controversy. The Florida State Health Department released a letter with a surprising new recommendation that contradicts standard of practice guidelines for measles outbreaks in two big ways:

Isolation. It stated that unvaccinated kids who were exposed to measles could continue to attend school. This is unprecedented. Those with no prior immunity need to isolate for 21 days.

Vaccination. It failed to recommend kids without immunity get vaccinated. Many parents don’t know that unvaccinated kids can still get protection from a vaccine within 72 hours of exposure. (Also, the standard of care is that if they get vaccinated within 72 hours, they can return to school as long as they don’t develop symptoms.)

Failure to isolate for measles is a major problem

The purpose of requiring unvaccinated children to stay home after measles exposure is to reduce, or rather stop, transmission.

Failure to do so significantly increases the chances of a prolonged outbreak.

We don’t require isolation for most viruses. If kids don’t get a flu shot, they don’t need to skip school if they were exposed to influenza. But measles is different:

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known on Earth. The R0—or the number of people an infected person can infect—is much higher than other viruses. Viruses spread exponentially, so in a population that doesn’t have immunity, just a few cases can become many very quickly. This means it takes a huge effort to contain it.

Measles is (largely) eliminated (although the U.S. status may change soon). In other words, it’s not spreading at a low level in other parts of the community. We want to keep it that way.

Measles has a long incubation period. It takes 5-21 days from exposure for symptoms to develop. So even if a child, especially an unvaccinated one, doesn’t have symptoms, they may be contagious and spread it to others, including in the community.

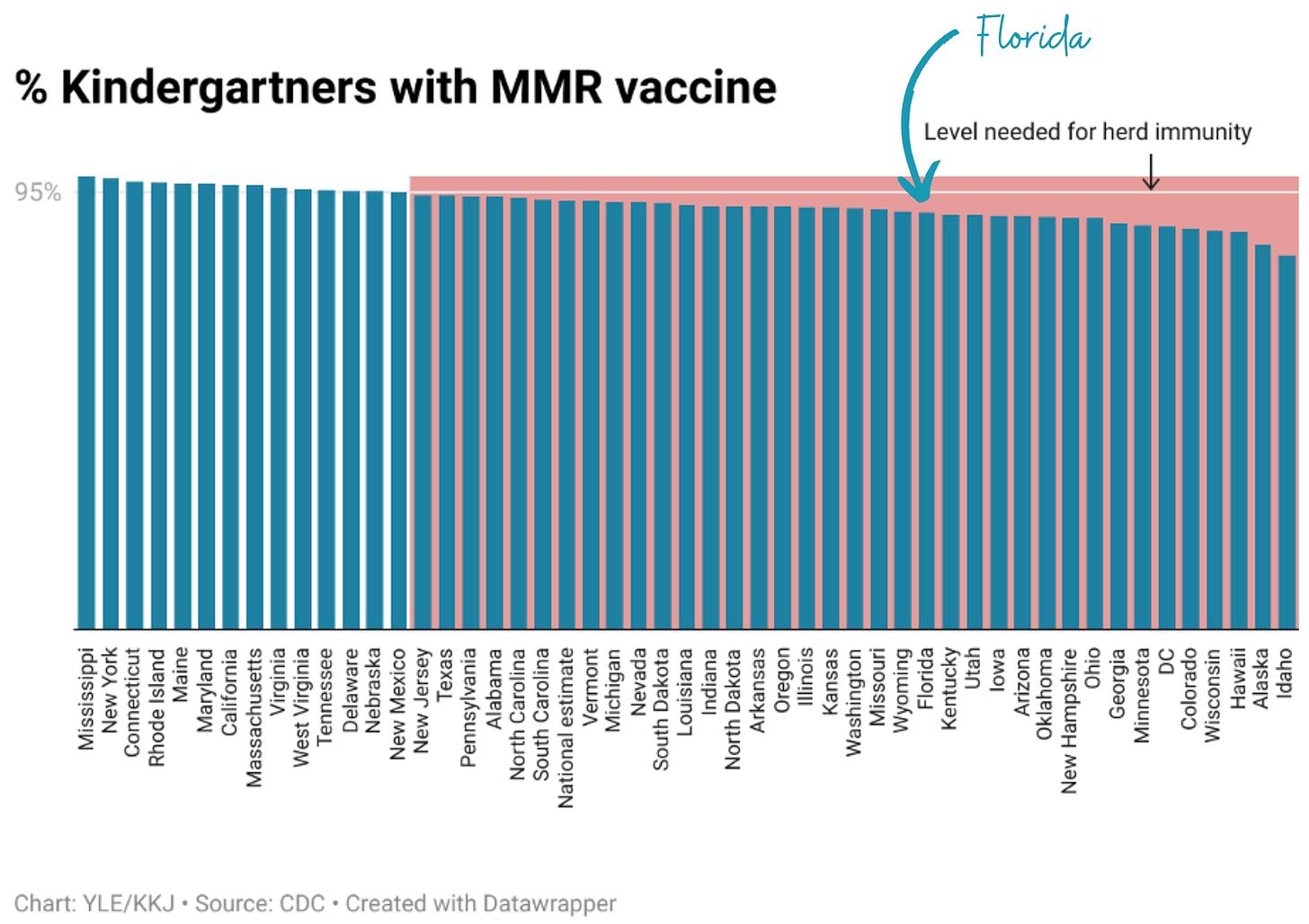

The FL letter tries to justify the decision to let exposed kids without immunity go to school by arguing that the vaccination rates in Florida are high. It’s true that 90% of FL kindergartners are vaccinated, which is high. But not high enough—because measles is so contagious, the threshold for herd immunity against measles is 95%. This means there are pockets in the school, other schools, and a community that measles could burn through.

Keeping kids home from school is hard, but sometimes it is very necessary

Missing school is not something health officials recommend lightly. But recommendations are always grounded in tradeoffs: disease severity, the potential for transmission, disruption to parents, childcare, productivity, economy, days of in-person schooling lost. We have all experienced quarantine and know what a disruption it is to our lives. It is only recommended when truly necessary.

As a parent, the most disappointing part of this letter is the lack of information on actions parents can take. For example, if they don’t want their child to miss school, they can get vaccinated, even after exposure. It will help reduce the severity of symptoms if infected, too. However, the window is short. Leaving this information out so parents don’t know is another level of deception.

Many have forgotten measles, but it is no joke

We have the privilege of forgetting measles because vaccines have largely wiped it out. But unfortunately, that privilege means many have forgotten just how bad it is:

It is extremely contagious. Among unvaccinated, 9 out of 10 people exposed will get infected.

It can make kids very sick. For people without immunity, 1 in 5 will be hospitalized, 1 in 20 will develop pneumonia (the most common way measles kills young kids), 1 in 1000 will develop encephalitis (infection of the brain, sometimes causing permanent brain damage), and 1-3 in 1000 will die.

It can cause “immune amnesia,” where the immune system loses its ability to fight other viruses that people were previously immune to.

Bottom line

Measles is not a new virus. We have been studying it for more than a century. There are reasons we have standards of practice, and it’s a slippery slope to think otherwise. Measles is no joke, and containing it should not be up for debate.

We hope parents and the community are paying attention. It takes a team approach to stop infectious diseases. This can mean strengthening immunization requirements or asking for bills requiring transparency about which schools have lower vaccination rates so parents can make informed decisions. The scary question is: What happens when community responsibility breaks down? We hope this is not the road we are headed down.

Love, KP and YLE

In case you missed it:

Kristen Panthagani, MD, PhD is an emergency medicine physician at Yale. In her free time, she is the creator of the medical blog You Can Know Things. You can subscribe to her newsletter here.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, M.P.H. Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, she is a senior scientific consultant to several organizations, including CDC. At night, she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health world so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

Florida’s surgeon general is a doctor. Why doesn’t whatever organization accredits doctors in Florida take action against him for violating accepted standards of practice?

Texas has long been known as "The National Laboratory for Bad Government" (Molly Ivins). Florida wants to claim the title. How else can one interpret this level of lunacy?