It’s been close to 6 months since the initial rollout of the fall (bivalent) booster. A lot of people are wondering: Do I need a spring booster?

The answer hinges on more questions: What is the purpose of vaccines? Does that purpose change depending on age or health status?

The purpose of the vaccines

Last month, the FDA and CDC made it clear that the primary purpose of vaccines is to prevent severe disease and death. Decreases in infection and transmission are a bonus at this point, and unfortunately, protection against infection is only temporary.

This makes sense for younger and healthier people. They are staying out of the hospital from COVID-19 for three main reasons:

Hybrid immunity. Younger people are more likely to have been infected. People with both vaccination and infection history have protection that lasts longer.

Less likely to have comorbidities. Their immune systems are less taxed.

Robust immune memories, particularly T-cells. Their thymuses (the organs that give rise to T cells) haven’t gradually degraded into useless blobs of fat, yet.

This means that even if antibodies are waning after 5-6 months, this is okay because protection against severe disease isn’t waning yet.

The story is different for immunocompromised and other very high-risk groups, like older Americans with comorbidities. The purpose of the vaccines for this group should also be to prevent severe disease and death. However, one could argue that in order to do that, we also need to prevent illness.

There’s one big reason for this: SARS-CoV-2 infection can exacerbate potentially fatal underlying illnesses, like heart failure or diabetes. Protection against viruses and underlying illnesses relies on antibodies to act quickly before the immune system is pulled in multiple directions. If it is pulled in multiple directions, it can lead to hospitalization and death.

Immunocompromised

Of the COVID-19 hospitalizations today, 25% are among the immune-compromised. (Immune-compromised make up 3% of the general population). There are really two subgroups to think about:

Non-responders to vaccines. At this point, this is a very small group of people, like organ transplant patients. Some people who did not respond to 2 or 3 doses eventually did respond to 4 or 5 doses. For the remaining non-responders, one could argue that there’s no point in boosting them, but the downsides of trying seem low.

Protection wanes quickly. The majority of immunocompromised people belong in this second group. The vaccine works, but just not as well and not as long. For them, vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization with the fourth dose peaks at 51% at 0-2 months, then drops to 28% by 2-4 months. (The bivalent booster may increase protection and duration, but we don’t know yet.)

There are few downsides to boosting this group every 6 months. It’s actually possible that the immune-compromised are somewhat protected against imprinting by virtue of their sluggish immune systems.

Older Americans with comorbidities

Those 65 years and older are contributing more and more to the proportion of deaths over time. Among adults hospitalized for COVID-19, 96% had at least one underlying condition.

This is because 2 of the 3 defense walls have more holes than those of younger people. Comorbidities also increase with age, which means the immune response in general is a lot more taxed.

So this is another group in whom we want to prevent infection in order to prevent severe disease.

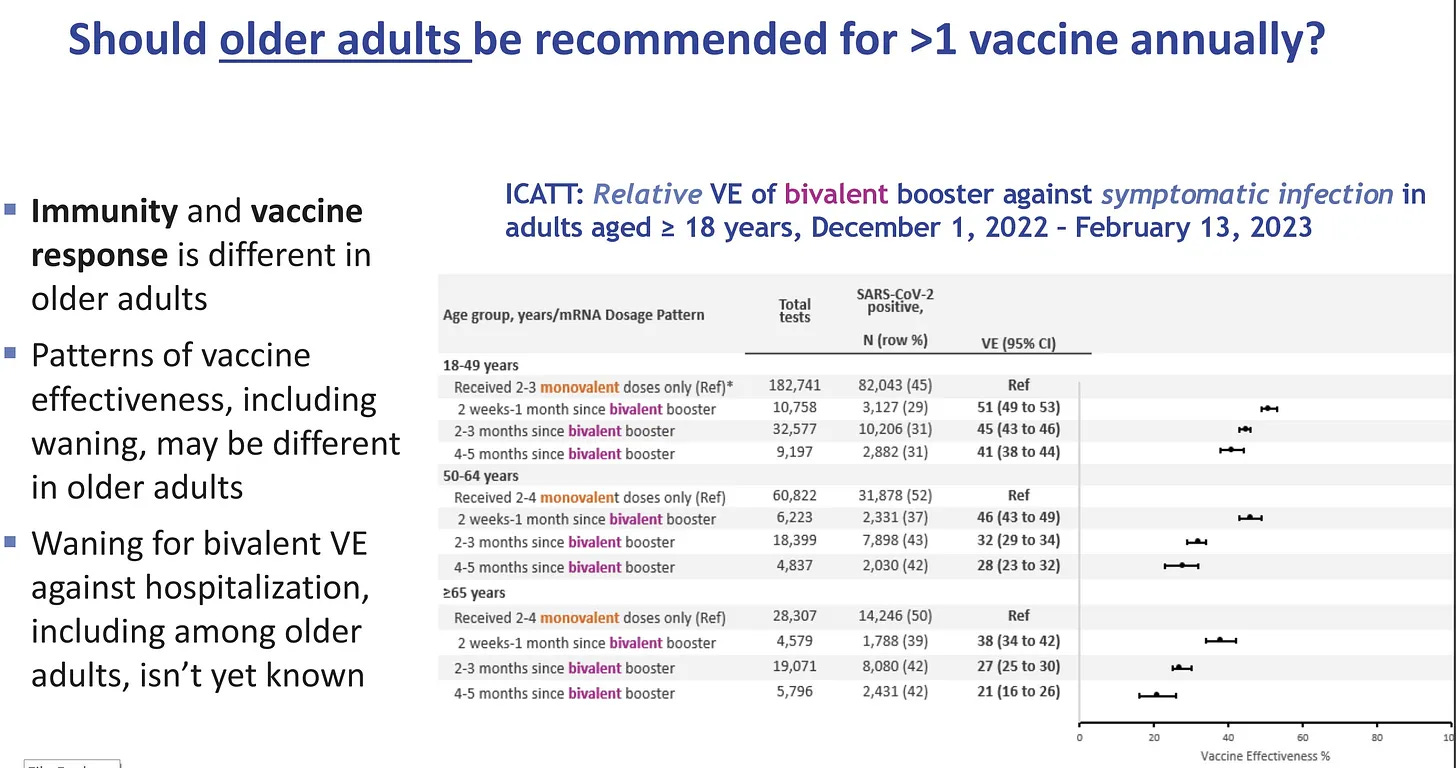

The latest data from the last ACIP meeting shows waning protection against infection among this group after 4-5 months.

The good news is that we clearly see that the risk of severe disease even in the very elderly dramatically declines with vaccination. In fact, very few people are in the hospital today who are up-to-date on vaccines. However, will this change with time? How much each booster helps (or does not help) incrementally is something that we really don’t have a good grip on prospectively.

What are other countries doing?

Canada and the U.K. have offered the bivalent vaccine to the following groups this spring. To our knowledge, this wasn’t based on any new data but rather a similar thought process as above.

Both countries used loose language: people “can” as opposed to “should” get a booster 6 months after the last dose:

U.K.:

People aged 75 years and older

Residents of care homes and other living settings for seniors

Those aged 5 years and older with a weakened immune system

People aged 80 years and older

Residents of care homes and other living settings for seniors or those with complex medical care needs

People aged 18 years and older who are moderately to severely immunocompromised

People aged 65 to 79 years, particularly those with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Will this be needed every 6 months until we start seeing predictable COVID-19 patterns? We don’t know. The WHO is meeting in Geneva this week to discuss global COVID vaccine recommendations going forward.

Bottom line

If you’re immunocompromised and/or an older adult with a comorbidity (and it’s been 6 months since an infection or last booster), a spring booster may be a good idea to stay ahead of the virus. Will it be official U.S. policy? We don’t know. There are rumors of FDA conversations happening behind closed doors. Hopefully, we will have an answer soon. But, as you can tell, it’s not a straightforward call.

Love, YLE and JF

Dr. Jeremy Faust, MD, MS is a practicing emergency physician in Boston, a public health researcher and policy expert, writer, spouse, and girl Dad. His Substack, “Inside Medicine,” blends his frontline clinical experience with original and incisive analyses of emerging data—helping people make sense of complicated and important issues. To subscribe to his newsletter, click this link.

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below:

My husband and I are 78 and nearly-76 respectively. Last month we went to a pharmacy where we're unknown, handed them our original cards for just our first shots and boosters, and asked for--and got!!--our 2nd bivalent vaccinations. We feel tremendous relief, and just wish we hadn't to sneak around to get this basic protection that's being offered in countries that are actually civilized (and not as political as the US GOP makes everything) about public health for their elders.

It is difficult to understand the “down sides” to boosting. I have never seen this articulated anywhere. What, precisely, are the risks of boosting? Additionally, with bivalent booster uptake being so low in the US, it is doubly frustrating to see vaccine doses expiring rather than be given to people who desperately want them. Much of vaccine policy is not making much sense these days. The long delays and debates on boosting and reformulating are tough to watch while the world burns with COVID waves, over and over.